On Jan. 7, 2015, four artists were gunned down by terrorists for expressing their political views through their drawings. Eight others were killed that day and four hostages during the week. What the terrorists pointed out by their heinous act is that art can challenge the status quo. Three artists whose work I have seen recently say that art must challenge the status quo.

Keith Haring was a street artist who painted throughout New York in the 1980s. When I walked into San Francisco’s de Young Museum, I anticipated seeing the barking dogs and radiant babies that had made him so popular. Keith Haring: The Political Line revealed a deeper vision.

Keith Haring was a street artist who painted throughout New York in the 1980s. When I walked into San Francisco’s de Young Museum, I anticipated seeing the barking dogs and radiant babies that had made him so popular. Keith Haring: The Political Line revealed a deeper vision.

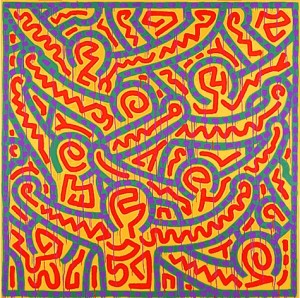

This exhibit showcased his responses to challenges of his day: nuclear proliferation, racial inequality, the excesses of capitalism, environmental degradation, electronic dominance, the AIDS crisis. Art, according to Haring, “should be something that provokes the imagination and encourages people to go further.” The role of the artist, he said, is to combat injustice and inequality.

Haring’s simple lines and bright colors contrasted with the complexity and darkness of the problems he tackled. His images, painted on huge canvases, on stretched tarps, on subway billboards, on statuary and urns, were part cartoon, part nightmare. Multi-limbed figures had televisions for heads and telephones for hands. Humanoids dangled from giant mouths. Figures morphed into dogs and dogs to monsters as they hounded black men in chains. Although painted thirty years ago, these works were a vivid reminder that we are facing the same issues today.

Keith Haring died of complications from AIDS in 1990. He was thirty-one years old. The last painting in the gallery showed a group of figures with their arms raised in defiance. Was it celebration? Was it anger? The purple drops seemed like tears. I left the museum thinking about what Haring accomplished in his short, prolific, and articulate life.

Keith Haring died of complications from AIDS in 1990. He was thirty-one years old. The last painting in the gallery showed a group of figures with their arms raised in defiance. Was it celebration? Was it anger? The purple drops seemed like tears. I left the museum thinking about what Haring accomplished in his short, prolific, and articulate life.

“The misconception of totalitarianism is that freedom can be imprisoned. This is not the case. When you constrain freedom, freedom will take flight and land on a windowsill,” says Chinese artist Ai Wei Wei, who was incarcerated in 2011 for speaking out against his government. Since then, he hasn’t been allowed to leave China. He developed the pieces for @Large: Ai Wei Wei on Alcatraz in his studio in Beijing; eighty volunteers assembled them on Alcatraz.

I took the boat from San Francisco to the former maximum security prison on a brisk winter day. The island is strange place with a with a long history: a Civil War fort, a jail for Southern sympathizers, a place where Native Americans who refused to attend “Normal Schools” were detained, a federal penitentiary holding some of the worst criminals in recent history, the site of Native American protest, and now, a National Park with gardens and spectacular views.

After climbing the perimeter steps, I entered the building where convicts had been put to work. A Chinese dragon kite looks directly out of the entrance towards freedom, its body trapped by the industrial structure. Its scales are covered with quotes from people around the world who have challenged their governments with words. Bird kites beat their wings against the barred windows.

After climbing the perimeter steps, I entered the building where convicts had been put to work. A Chinese dragon kite looks directly out of the entrance towards freedom, its body trapped by the industrial structure. Its scales are covered with quotes from people around the world who have challenged their governments with words. Bird kites beat their wings against the barred windows.

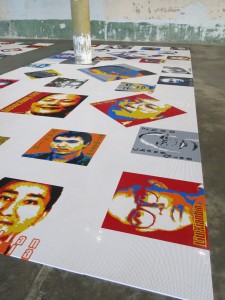

In the next room, brightly colored images cover the floor. Each image is the face of someone who currently is in prison for speaking out. The carpets are made of thousands of lego pieces. A printed guide tells who each person is and what their words have done.

In the next room, brightly colored images cover the floor. Each image is the face of someone who currently is in prison for speaking out. The carpets are made of thousands of lego pieces. A printed guide tells who each person is and what their words have done.

The third installation can only be seen through the small cracked window panes of the gun gallery where guards maintained control over the prison dining area. It is a large winged creature made of Tibetan reflective cooking panels and metal tea pots. Compressed inside this space, it is seemingly wounded, unable to raise its head. Ai Wei Wei says, “If my art has nothing to do with people’s pain and sorrow, what is ‘art’ for?”

I visited the High Art Museum in Atlanta not knowing what I would get to see. Fortunately, Gordon Parks: Segregation Story was the premier exhibit.

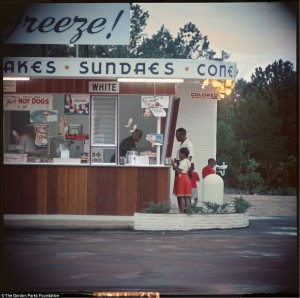

In 1956, Life Magazine published Gordon Parks’ landmark photo essay called The Restraints: Open and Hidden. Parks, the first African American photographer hired by Life, followed three families near Mobile, Alabama as they went about their daily lives. He wanted to show images most of the country wasn’t seeing: real people facing the damaging effects of racial discrimination. Some of the pieces in the museum were from that essay; others had been discovered only after Parks’ death at ninety-three in 2006.

In 1956, Life Magazine published Gordon Parks’ landmark photo essay called The Restraints: Open and Hidden. Parks, the first African American photographer hired by Life, followed three families near Mobile, Alabama as they went about their daily lives. He wanted to show images most of the country wasn’t seeing: real people facing the damaging effects of racial discrimination. Some of the pieces in the museum were from that essay; others had been discovered only after Parks’ death at ninety-three in 2006.

Each large color photograph captured a prosaic event: a grandma window shops with a child, a mom takes her young daughter out, a dad buys an ice cream cone. The image is rendered in beautiful color and exquisite composition. But the seeming sweetness of the moment is set within the horrors of segregation. This juxtaposition made the exhibit deeply disturbing and powerful.

Each large color photograph captured a prosaic event: a grandma window shops with a child, a mom takes her young daughter out, a dad buys an ice cream cone. The image is rendered in beautiful color and exquisite composition. But the seeming sweetness of the moment is set within the horrors of segregation. This juxtaposition made the exhibit deeply disturbing and powerful.

I watched a young father looking at these photographs with his three little boys. They asked him question after question about what they were seeing. I wondered what, as a black man, he was saying to his children. How would he explain our country’s history to them? I was acutely aware of my whiteness. I felt shame for our country then and shame for the people whocontinue to define worth by skin color.

Gordon Parks said, ”You know, the camera is not meant just to show misery. You can show things that you like about the universe, things that you hate about the universe. It’s capable of doing both.” This exhibit did both.

What is leadership? The ability to raise the heat on issues that need to change and the willingness to put yourself on the line to change them. Anyone from any stratum of society can lead. Artists, too, can lead, not just provide visual entertainment. In fact, artists may be the only ones who can freely shine a light on our country’s ill and the world’s oppressors.

The acts of terror in Paris last month show us the danger. It is a rare artist who has the vision and talent and courage to do this. Most of us haven’t a clue where to begin, but it may be our responsibility to learn. As Ai Wei Wei said, “Freedom is a pretty strange thing. Once you’ve experienced it, it remains in your heart, and no one can take it away. Then, as an individual, you can be more powerful than a whole country.”